So what is the best way to go about investing in bonds? This is a questions that investment professionals often get wrong. Many like to tout individual bonds as a premium offering and will try to sell you on the advantages of owning them over bond mutual funds that smaller, less important investors are forced to slum in.

Bond prices fluctuate over time. As the prevailing interest rates go up, the value of bonds already on the market go down because the interest they pay relative to the market is less attractive. I’ve heard many advisors tell their clients it is better to own individual bonds and avoid bond mutual funds because if rates are rising — as they are currently expected to — the price of the mutual funds will go down.

Well guess what? So will the price of your individual bonds.

These advisors might give you a line about how that doesn’t matter so long as you hold the individual bond to maturity because you will get par value for the bond at that time. But it does matter, regardless of whether or not you hold it to maturity. If you have a bond that’s only paying a 2% coupon, but the market is currently offering 4% for bonds of a similar credit and maturity, you are missing out on that extra 2% and your bonds are worth less on the market than par because of it.

Even if you plan to hold the bond to maturity, there is no guaranteeing this will be the case. There could be a need to raise a significant amount of cash for an unforeseen expense and bonds may need to be sold at whatever the market will give you to do it. Market movements might also require you to occasionally rebalance your portfolio to maintain the appropriate asset mix for your risk comfort-zone and investment objectives, potentially requiring you to sell a bond or two.

And what if the credit quality starts to deteriorate? Are you going to want to hold onto a bond that doesn’t mature for ten years if it is issued by a company you now think might be bankrupt in five?

Bond markets are always in flux. There are times when you want shorter maturity bonds and times when you want a longer duration. Times when corporates are attractive and times when the safety of government bonds is where you want to be. Times when higher credit risk is worth it and times when it’s not. The point is, this is a space where active management by a skilled manager can pay off.

This way of thinking also overlooks the fact that you should have more than one bond in your portfolio, and in order to maintain appropriate duration of your portfolio those bonds should not be maturing on the same date. I saw a number of bond portfolios that weren’t properly diversified be permanently impaired during the financial crisis because of a single default. If you are playing in the individual corporate bond or municipal bond space I would recommend having at the very least ten bonds from different issuers before I would consider the portfolio diversified.

So even if you know the value of the bond will be par at maturity (assuming the issuer does not default), your bond portfolio as a whole will never have a certain value. It will be a basket of securities just like a mutual fund, only less diversified and without a qualified manager always looking over it.

If that’s not enough to convince you to stay away from individual bonds, here is one more. The bond market is one of the last great places where Wall Street can screw the individual investor, and the investor likely doesn’t even realize it.

Best execution in the stock market has been easily and cheaply accessible to the little guy for years, but the costs aren’t so straightforward with bonds. Most individual investors don’t realize when they go out and buy a bond the price they pay for it has an embedded markup. This is how bond dealers make their money; by charging you more for the bond than what it’s actually worth. And they get you on the back-end as well when you go to sell by buying it for a marked-down price.

There is certainly nothing wrong with making money for providing this liquidity, but this isn’t a space that takes kindly to Joe Schmo investor. And best of all for them, they don’t even have to tell you how bad of a pounding they just gave you.

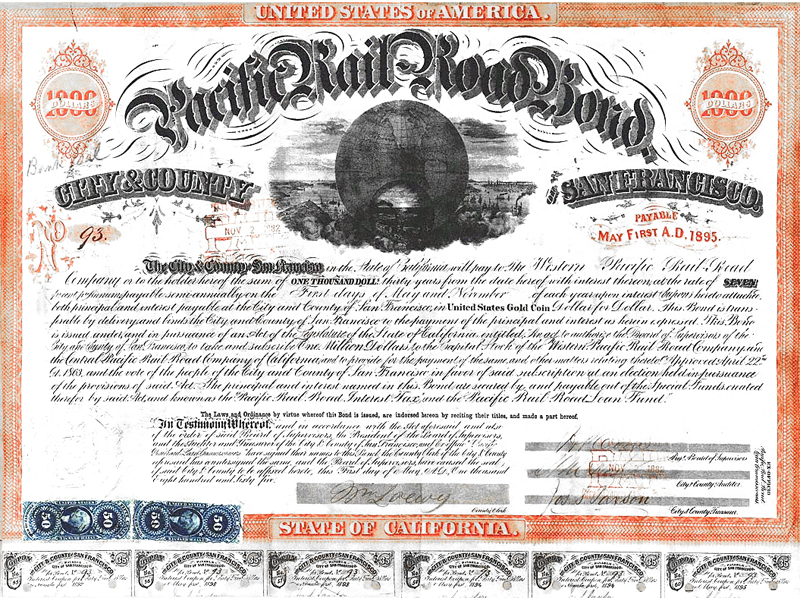

With the exception of Treasurys the bond market is a lot less liquid than the stock market, especially in the municipal bond space. Research by the Securities Litigation & Consulting Group of Faifax, Virginia showed that between 2005 and 2013 the median markup paid by investors buying municipal bonds sized $25,000 or less was 1.79%, with the 95th percentile paying 3.48%. With 10-year muni bond yields at only 2.32% right now, this means you could be giving up more than a year’s worth of interest the moment you buy one of these.

Source: Securities Litigation & Consulting Group

Source: Securities Litigation & Consulting Group

The pricing doesn’t get reasonable until you hit the $500,000 mark, and really it’s only at $1,000,000 where you’re getting treated well. So unless you’ve got at least $5,000,000 for your individual bond portfolio, I suggest you stick to mutual funds and ETFs. By investing in the right fund you quickly and easily go from being the tiny fish who gets taken advantage of to one of the biggest sharks in the ocean, and that is well worth the fund expenses you’ll pay.